Welcome back! In case you missed it, Chapter 13 was published last year before I serialized the book here. However, you don’t need to read it in order to listen 🎧to this one. Thanks!

We relocated to one of America’s armpits because the naked man in Mom’s bed stuck around. Unlike the fireman, she decided to stay with Tim when the Army sent him to a new location or permanent change of station (PCS). But I didn’t want to move. My class was going on an end-of-the-year camping trip, and I just got a new blue bicycle.

So we moved from gorgeous green Mililani to boring brown Barstow. I went from having friends to having none. We went from residing in a dynamic neighborhood with plenty of kids, to living on the edge of a desert town, a colorless pit-stop known for being halfway between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. Tim didn’t even put us in a proper neighborhood. The houses were in various stages of becoming and tumbleweeds blew by—just like in the cowboy movies.

This was also when Larry and I would start to pull apart, when I’d become a teenager, locking myself in my room, listening to throbbing rock music, wiggling the mascara wand, and realizing I wasn’t as pretty as the girls in the magazines. But until I crossed that line completely, we walked side by side exploring the Mojave desert behind our house.

But we couldn’t go too far, the landscape was too unforgiving, too monotonous, too unfortunate if we got lost. We flipped rocks to see if we could find any scorpions or lizards. We saw a jackrabbit once, but in my excitement I accidentally put my hand down on a cactus.

The desert was a dangerous place, that’s also incredibly hot and dry. For the first time in my life, I used lotion on my legs and Vaseline on my lips and up my nose to prevent nose bleeds.

Larry watched a good amount of cable television. His primary focus was Nature and other PBS programs. He became the focal expert on the habitats and feeding practice of all living things. Flexing his sponge-like ability to absorb information, he recollects dates, times, and seemingly minuscule facts to the great annoyance of other family members. His propensity to recall has been used as incriminating “evidence” for all wrongdoing against him. So, while I got stuck with the amnesiac flux gene that plagued me long before I ever inhaled, Larry could have been a singer, actor, or a Jeopardy! contestant.

And while Larry could find some comfort in front of the TV, I had to find something else or to use the teenage expression “die of boredom”. When we drove to the nearby town of Victorville to go to the mall (aka civilization), I wandered into Waldenbooks out of sheer desperation to find something to do and shave off time in a land of loneliness and dust.

I searched around the bookstore peripheries, running my fingers over book spines, covers, and names before parking in front of the Young Adult section. Sweet Valley High, Cheerleaders, Nancy Drew, Couples, Seniors, and Sunfire series winked at me and made cross-my-heart-and-hope-to-die promises. Soon I was infatuated with reading and writing, no longer melancholy for bygone days and entertaining future fantasies of what lay ahead.

When folks think of California, they assume it’s some sort of Asian stronghold, but they’re wrong. Even when I moved to Chico in 2005, there weren’t many others. Small towns in the Golden State are usually predominately white.

In 1985 when we moved to Barstow, there weren’t other Asian kids around. But even before I stepped into the sixth grade classroom, I knew things were going to be different. The walk to school was bleak, barren, and extremely windy, and we didn’t make that mistake again.

On my first day, joining the class in May, I was surprised to see a room filled with maybe nine kids. Back in Hawaii, my homeroom class alone had about 25 students and that was just one of four other sixth grade classrooms.

“Hello everyone!” The teacher chirped. “I’d like to introduce Lae-knee,” and thus began the long chapter of people saying my name incorrectly.

“She’s just come from Hawaii!” and the chapter on how excited people get when they learn I’m from Hawaii.

“It’s Law-nee. Like Loni Anderson.” I mumbled.

“Oh, how cute.”

I looked at the children staring back and took a seat hoping to find friendship among them.

But the firsts were starting to stack up, and now I discovered what it was like to be a minority and the new kid at school. It’s hard to say why they didn’t talk to me. Over the years I learned that folks like to stay within their own friend groups. Some are weary of outsiders, and others are too lazy to bother. I wondered how my younger brother was fairing, but he was located in a completely different area of the school.

As far as I could tell, we were the only Asian students running about. I might have seen one in kindergarten, but I can’t be sure. Larry has a more interesting look to him. That is, he doesn’t look as Chinese as me. He could pass for Native American, he looks more Southeast Asian and has a darker complexion. Plus, he’s a boy. I think third grade boys were more accepting.

During recess, no one would play with me. Then the teacher intervened. I saw her whispering to one of the girls while looking over at me. Great. Now, I’m a charity case.

I was invited to play four-square until I was out, and when it became clear that I wasn’t going to be invited back into the game, I went to the building again. I watched the other children have fun in the sun. Once, I went back into the classroom until the teacher told me to go out and play.

So, during recess, I walked along our school building and eventually found another girl who was by herself. She was an outcast as well because she was so different-looking than everyone else.

She looked like a freshman in high school or at least in junior high. She had huge knockers and a light mustache. She dressed wildly, very ‘80s Madonna, but since she didn’t have as much money as the Material Girl, her jewelry was all plastic. She was wearing more Mardi Gras-looking beads than a wholesale outlet. Her wrists were adorned with stacks of jelly bracelets. Her look was excessive, over the top, and yet ironically, she seemed painfully shy.

“Hi,” I said as I approached her. She was as far as one could be from the playground. It was quiet.

She looked up from the paperback novel that she was reading. She smiled behind her plastic rimmed glasses. “Hi.”

“What are you doing?”

“Reading.”

I moved a little closer. “Can I see?”

She showed me a Harlequin romance book.

“Oh. Is it any good?”

“It’s okay.”

“I like to read, too. I read Sweet Valley High books.”

After that, we hung out. She wasn’t much for running around like the other kids, so we bonded over books and our favorite CBS soap operas. At Mililani Waena, I wasn’t much for sports then either, preferring to hang out with just one friend, Janet Craig.

At the cafeteria, some boy from another class sat down next to us and made a snide remark about her breasts. She sat there with her head down. I told the little brat to get lost, but he continued to gawk at her chest, resting his head on his hands, treating her like a zoo animal, then he got up from our table.

“What a jerk,” I muttered. “You should stand up for yourself.”

She shrugged.

“They are rather large.” I pointed out.

And I was rewarded with a giggle.

The one time the girls did talk to me was to ask if I liked any of the other boys in class. I said no, and subjected myself to being asked a lot of pointless questions until they seemed hell-bent on matching me up with someone, and that somebody was William. I considered his dark hair and freckles. His slim frame. He seemed, alright.

I didn’t think much of the girls or William until I remembered when we went to the softball field for PE class. Why yes, I was the last person to be picked, along with my fellow outsider.

When it was my turn to bat, I stood there, and swung it like I had seen on TV.

The class laughed.

“Haven’t you ever played softball before?”

“No.”

William came up and gently put his arms around me to show me how to swing a bat.

“Oh.” I was surprised by the intimacy, but thought he was simply being nice.

“Thank you.”

Later, I realized why the girls were being smirky, and later still, I figured out that one of my classmates was jealous.

Junior high was better. Mom put us in Barstow Christian School. Seventh and eighth grade was a combined mishmash of minorities and whites. Two of the Latino boys in my grade made private lewd gestures at me that I didn’t understand, but I knew they were inappropriate. They’d call my name, and when I turned around, they’d do it. I’d look at them with disgust, and they’d laugh.

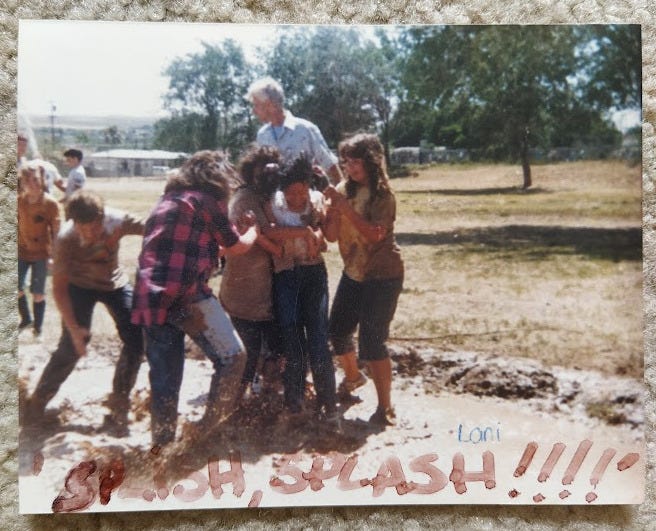

There weren’t many of us, so the girls hung out together and so did the guys. They usually played basketball while we were on the sidelines enjoying feminine activities such as sitting on the benches or going for leisurely strolls around the court like we were Victorian women.

Shannon was our most popular girl. She was blond and a cheerleader, but the boys were mean to her, too, calling her “thunder thighs”. But I wasn’t the outcast anymore, Sharon was. We all tried to be nice to her, but she seemed content to be on the fringes in her own head-space.

Reading made me fearless. I devoured stories of brave young women, taking chances, learning from their mistakes, and doing what’s right. Despite feeling the most self-critical over my appearance, I asked boys to kiss me, slipped nameless notes in my crush’s locker, and scheduled a meeting with our school pastor because I wanted to tell him I believed in hell. Rock bands on MTV like KISS and Twisted Sister convinced me.

During my eight grade year, I tried out for cheerleading and somehow became captain. At recess, I went up to Tony who pissed me off, stood inches from his face, and said fuck you! All our friends oohed, but then afterwards I regretted my actions, it had been too much, so I apologized.

When we were living in Barstow, our adult supervision was mainly tied to Tim, who was maybe 25 at the time. His pot smoking brother, Tracy, squatted at our abode for awhile.

This isn’t to say Mom wasn’t around. She was, but she was busy working at The Golden Dragon, quite possibly the most common name for a Chinese restaurant in the US besides The Great Wall.

She found Thai friends in the-middle-of-nowhere as unbelievable as that might seem, and they all worked in this diner-style restaurant off of Main Street. It was scary to cross Interstate-15 after school to reach my mom, until we got used to it. My first diary entry was about a car that crashed into The Golden Dragon. Luckily, no one was injured.

Sometimes we hung out at The GD, but it was pretty boring because the restaurant never seemed busy. And unlike other restaurants Mom would work at, we couldn’t hide in the kitchen. No, The Golden Dragon was probably a fast-food joint turned American fried rice and sitting in vinyl booths gets real old after about 20 minutes.

Tim largely hung out with his army buddies who had nicknames like Butch and Hawk. Butch was overweight. Hawk was kind of cute in that way girls like, innocent-looking. Tim’s nickname was Ace, but they also called him Too Tall Tim because he’s 6’4 and built like a string bean. He subsisted on high-caloric fast food meals, cigarettes, and beer.

Anyway, Butch and Hawk’s house was spacious with a large swimming pool in the back that had a massive inflatable crocodile, diving board, and a sign that stated, “I don’t swim in your toilet, so don’t piss in my pool”.

The kitchen appeared clean except for the rich and abundant amounts of thirsty-looking dishes piled up in the sinks. The excavation and removal process would beyond question involve rubber gloves, eye-protection, elbow-grease, and something caustic like lye. It wouldn’t have surprised me if they took all of the dirty kitchenware and hosed it down on the front lawn.

Like the pool, the homemade bar was one of the selling points of the home. The Bartles & James wine cooler guys’ cardboard cutout was a particularly clever touch, but eventually it had to be hidden because whenever Butch got up to pee in the middle of the night, he thought they were real people. He might have punched or attacked the cutout once or twice.

The bar was the place that I liked to hang out because it had thoughtful touches like the rubber chicken tied to the bottle opener and graffiti that looked good.

I used to read what was written on the wood. I watched the lettering move from left to right and grow with each visit. They were conscientious of how they decorated it. Some messages were puzzling like the one that had a drawing of a wrench next to it. I asked Tim, “What does ‘torque my nut’ mean?”

He chuckled, but never answered my question.

There were the obligatory posters of bikini clad babes for Budweiser around the house, and when I wandered into Hawk’s room, because I had a crush on him, I paid attention to all his ski posters.

Besides Butch and Hawk, GI’s who came for a visit or to party looked over at Larry and me, ages 13 and 9 and wondered what the heck we were doing in this bachelors’ pad.

“What’s with the Chinese kids?”

“Ask Tim. They’re his.”

“Hey Tim, why do you have two Orientals?”

He took a swig of Coors, his favorite, before answering. “I found them.”

And so began the ridiculous tale that grew more stupid with each retelling to every idiot who fell for his fantastic yarn.

“WHAT?”

“Yeah,” he took a drag from his Marlboro Red. “Can you believe it? Found them on the side of I-40, found out that their parents had abandoned them.”

There was a crowd around him now.

“Shi-it...”

The young men looked at Tim and back at us as if he was some kind of goddamn saint.

“No fucking kidding?”

What else could he have done? Leave us by the side of the road in the middle of the desert? No, he did the right thing, he stopped the truck and picked us up. And now look at them, two Orientals, lost and found, and filled with wonder at their new surroundings. You would have done the same thing.

Decades later, after I learned what he had said behind our backs, I asked, “Did you ever tell them the truth?”

I waited for him to take a drag and blow out the smoke. “Nope.”

P.S. Thanks for reading and/or listening along. Please share, like, subscribe and leave a comment! Appreciate it. xo

Lani, this powerful, raw, beautifully told chapter carries memory’s weight with such clarity and courage. I’m so sorry for the loneliness, cruelty and casual racism you endured so young. Your family deserved kindness, belonging, truth and it’s painful to me that they were often missing.

The solace you found in books, friendship with outsiders, and your own voice is heroic. For your writing turns pain into art, and I’m pleased you shared it. That moment of being “lost and found” isn’t just a turn I phrase … it’s such a tender, complicated truth wrapped in resilience and survival.

You and Larry were thrust into a strange world, both as treasures and outsiders, navigating with deep courage. Being “found” meant entering a new struggle that demanded resilience and self-discovery. Your story carries this tension honestly and deserves to be held gently and seen fully.

Never stop writing, my dear friend! 🙏💖

Ha, wild! And I was relieved that this story didn't turn dark--you and your brother hanging with 20-somethings. "Reading made me fearless." is perhaps my favorite line ever!