2. My father, the dragon

Welcome to the third installment of Misfortune Cookie

My grandmother, Jeanyeh, was on a train to Peking. It was most likely 1945 or 1946, as she was traveling during a window of peace talks between the Nationalists and the Communists. It was the end of World War II and eight years of fighting the Japanese, a war controversially known as “the Asian holocaust” due to the catastrophic amounts of bloodshed and war crimes.

Yet, despite growing up in war-torn China, my grandma never complained, never mentioned it, choosing to protect her granddaughter instead with stories of achievements, like the time she traveled to Japan because she won a school contest, or her jobs as a radio announcer, teacher, and newspaper reporter. If Mom’s tales seemed tall, of poverty and leftover rice, Grandma’s were even taller, of privilege and protection.

It was on this fateful train ride to Peking that she met Ju Pae Xing, a captain in the Chinese Nationalist’s Air Force. He was very tall, extremely good-looking, and arrogant.

“Your father looked just like him,” she told me passionately, with that intensity and drama I’ve come to know as simply the way she spoke.

But Grandma must have stood out herself. She, too, was tall and with an hour-glass figure. Her eyes bright, her smile generous, and her skin pure white.

And even though Ju Pae Xing was 30 years old, 15 years her senior, two months later, they were married.

Despite coming from a well-to-do family, she needed his military status for protection, and only those who were affiliated with the military were able to survive. (Well, at least very well.) Her marriage secured safe passage for her family and herself throughout China, and eventually (I believe) aided in her escape.

“Your grandfather was a pilot and parachute jumper. He was educated and trained in the United States. He escaped death from the Japanese many times due to his cunning martial art skills.”

I wondered out loud whether these stories were magnified in order to impress her granddaughter. And she looked at me as if I was the crazy one to doubt that my grandfather was the Jackie Chan of his time. Her stories, like my mom’s, transfixed me like a book or movie, and I regret that I can’t ask her anymore questions, and that the notes I took were so sparse. Instead, in that moment, I silently wondered how her memory was holding up.

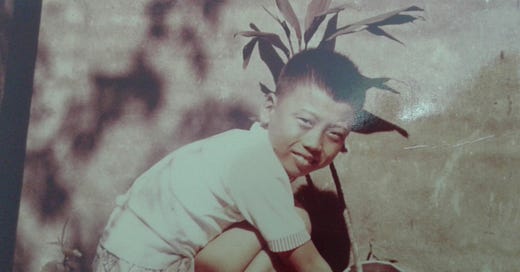

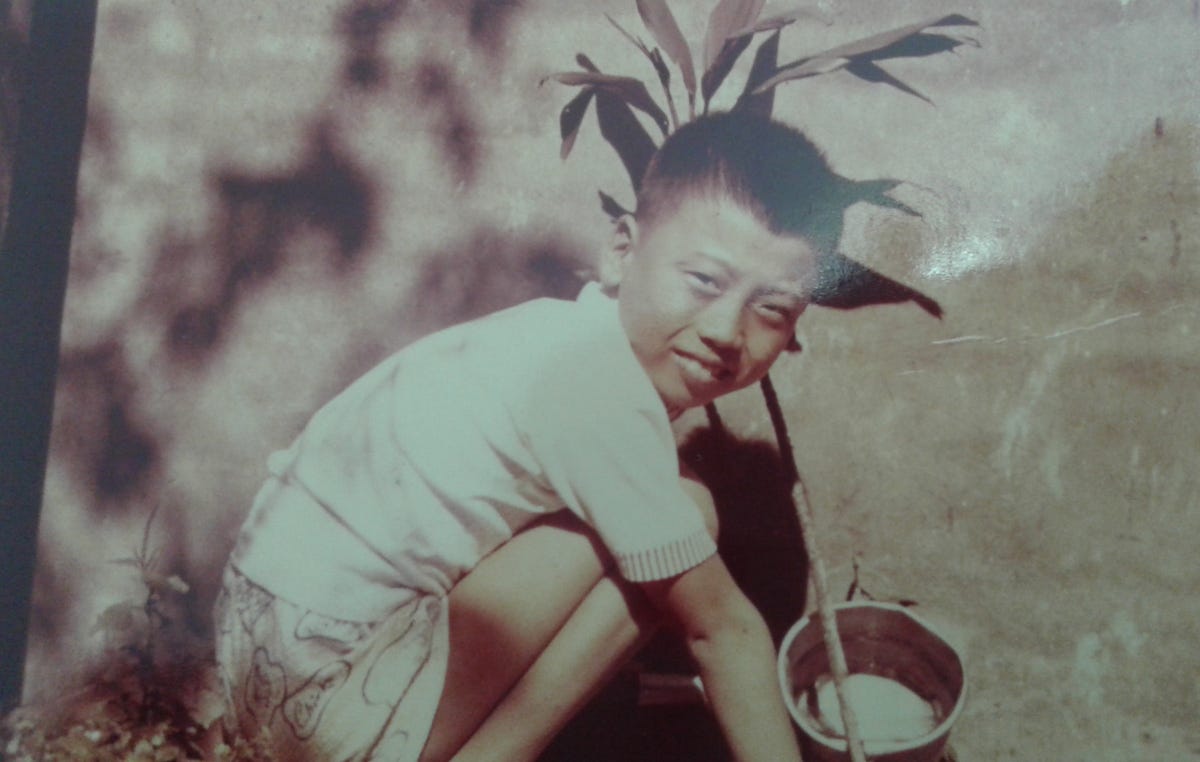

In 1947, my father, Hwa Lin, which means “elegant dragon,” was born in the capital. He was a good baby who was mainly looked after by his aunt. Grandma worked, even though food, housing, and a soldier was assigned to officers’ families to help with cooking and cleaning. Ju Pae left her with too little to survive, so she lied about her age and worked, which wasn’t as challenging as it might have seemed since she spoke Beijing Chinese, Mandarin, and Japanese.

Meanwhile, paper money was useless, unemployment soared, and the Communists numbers swelled. Unknown numbers of Chinese became homeless, and refugees, who were starving under years of war and strife, poured into the cities.

The family moved often to stay ahead of the fighting. At some point, perhaps soon after Dad was born, they traveled from Peking to coastal Tianjin, where they boarded a submarine to the Nationalist Party’s stronghold, Nanjing. There isn’t a lot of room in a submarine, but if travel over land was too dangerous, then an “underwater mousetrap” would have to do.

Grandpa wasn’t around much, but when he was, he hit her, beating into my father a memory of what he never wanted to become, so that when it came to Mom spanking us, he wouldn’t allow it. Eventually, Grandma fought to get a divorce, but this wasn’t easy, much less heard of, as typically it was the men who filed for divorces.

Most Nationalists fled China for Taiwan during 1949-1950. I believe my family left in 1949, along with the other 2 million. Grandma and family emigrated from Shanghai to Taiwan by boat, and she wouldn’t return to her homeland until about 40 years later. However, it was a disappointing visit, where she was treated like an outsider, as she was no longer considered Chinese.

But once in Taiwan, the family moved around quite a bit (14 different houses). They lived in Tainan, Kaohsiung, and Keelung, to name a few, in what I can only assume was an attempt to find a new home. During the next ten years, Taiwan would be well under the Nationalist’s government and would receive significant funding for education and military protection from the United States.

A means to settle down finally came through a debt owed to Grandma’s father when she became the co-owner of a restaurant that served American food in Taipei. She claims she ended up paying off Ju Pae for the divorce through her work here. Specifically, it’s how she gained custody of my father because in China the law maintained that children of a divorced couple should go to the dad. I’m not sure how this arrangement was made as Ju Pae had stayed in China. Later, it was rumored that upon learning of his son’s death, he disappeared never to be seen again.

Nevertheless, the restaurant in Taiwan provided not only economic stability, but was also where Grandma met her next husband. Kenneth Elvis Cox was an enlisted airman in the US Air Force. His father was a British Navy admiral and his mother, a German, was a nurse.

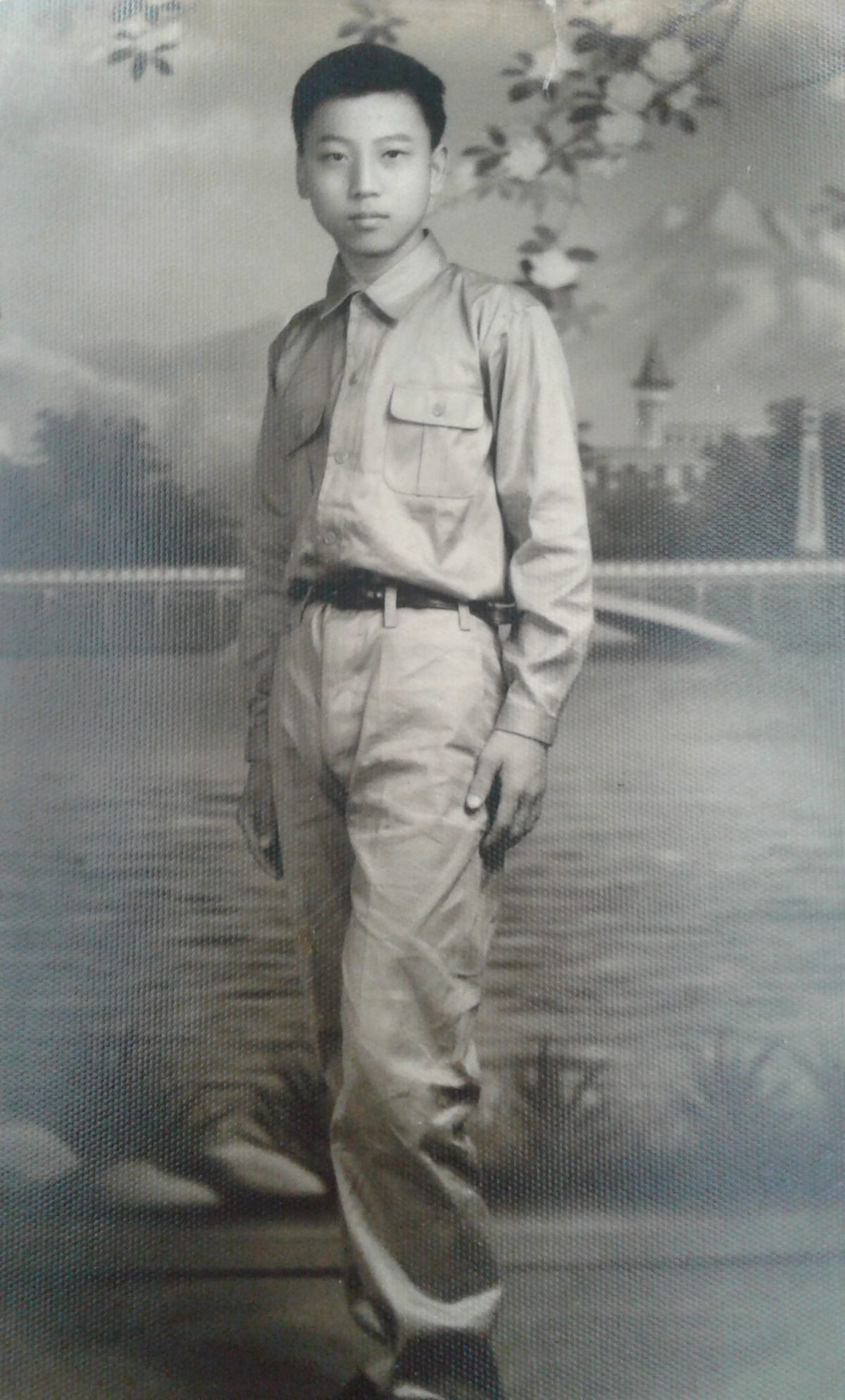

But despite the fact that Ken fell in love with Jeanyeh, to be known as Jean, she wouldn’t marry him until he became an officer. So he graduated from university, learned Chinese, and was kind to her family. After they married, he adopted my father, and that’s how we have a Western last name. In 1962, when my father was 15 years old, the US Air Force stationed the family in Tachikawa, Japan where Ken and Jean had a girl, who they named Karen. Then, they moved to the United States.

What a treasure to have heard these tales from your grandmother, a reminder of how much migration and survival are a continuous thread in our collective human histories.

Another captivating instalment! I listened for the first time now and loved it, will continue listening to the next chapters too :)