These installments are read by the author. For the previous chapter, please click here. It should be noted, however, that these essays can be read on their own. Thank you listening, subscribing, liking, and sharing.

After the hospital, I don’t remember anything else until his casket was loaded onto a military cargo plane, a C-130E. Since he died while serving in the US Air Force, we traveled with his body from Thailand to Clark AFB in The Philippines, and then onto what I assumed was a commercial flight J252 to Guam, and finally to Hawaii. But it’s the cargo plane trip that I remembered. We sat in the front just behind the two pilots, who seemed like young and friendly men.

When I had to use the bathroom, I was told to go to the back. It was then that I realized I had to walk by it—his casket, the coffin, and it was black. And I wondered why it had to be by the toilet. I couldn’t help but stare at it. I thought about his body lying in there, and then I remembered why I was there, in the back of an empty plane, and tiptoed around it, always keeping my eyes on it. Finally, I reached my destination and drew back the curtain that enclosed the toilet.

When we were sitting behind the pilots, I’d occasionally hear the coffin sliding around. It was such a large, empty plane just for us. I wished they had secured him. Now, you might think, it didn’t slide around, that’s just a young girl’s overactive imagination. But I know that it did. When the plane moved, it moved. I heard it. We all did. I could see the pilots looking at one another. I turned around several times in my seat to check to make sure he was okay.

“Hey,” one of the pilots said. “Would you like to fly the plane?”

I turned back around, and stared first at him, and then at the other pilot. “I don’t know how.”

They laughed. “We’ll show you how. It’s easy. C’mon up here.”

Looking over at Mom, I saw that she approved. She held Larry in her arms, but she was somewhere else. Her smile was for me though, and I took it as a “yes” and walked up between the pilots.

One of the men stood up and told me to sit down in his seat. Then he instructed me to put my hands on the “steering wheel”.

Carefully, I wrapped my five-year-old hands around the yoke, and I looked out at the sky around me.

“You see? Nothing to it, kid. You’re flying.”

I looked up at him. “I’m flying?”

“Yes.”

Grinning with delight, I looked back at Mom. “I’m flying!”

She smiled.

My legs were swinging back and forth. I gained confidence and began pointing to the instruments and asking questions. But after what seemed like a long time, I wondered when the pilot was going to return. My arms and hands were getting tired, and I secretly began to suspect I was doing all the work for the crew. But finally, the pilot returned to his seat, and we landed.

I used to look up at planes and think about where they were going, and as I gained a better sense of direction, I learned which planes were landing or leaving Hawaii.

It didn’t help to later learn that if Dad had lived, the military was going to station us in New York. In fact, we were supposed to have gone to New York City for a visit after Thailand. He went to high school in Syracuse and was most likely looking forward to revisiting his old stomping grounds.

From time to time, I contemplate how different my life would have been had he lived. I know, it’s a bad idea, but it can’t be helped. I’m certain I wouldn’t recognize the other me. I’d probably be one of those high-achieving Asians. Mom’s English would have improved, and she would have gone back to school. Dad was also on the brink of being promoted from captain to major, and those formative childhood years would have been on the East Coast as opposed to the island of Oahu.

Growing up on an island felt like the world went on without you, but at the same time you’re told how lucky you were to live in Hawaii. This is something you won’t realize until you’ve left because Hawaii is unique in ways that you don’t understand until you’ve left her white sands, warm waves, and diverse people.

We grew up with nautical terms like leeward and windward to indicate direction and trade winds, and Hawaiian words like mauka and makai to refer to mountain and ocean side. We listened to surf reports because it was on the radio, and while the weather was typically 86 degrees with a cool ocean breeze, we still had to pay attention to high winds and hurricanes.

We learned that Hawaii was a glorified military base which created an us (locals) versus them (tourists and military personnel) mentality, but since I was both a military brat and a local I guess that made me an all-around team player, or Benedict Arnold.

Ethnicity was also our compass, something we openly discussed, asked about, and knew. This didn’t make us a Happy Days round-the-clock sitcom, but more like an All in the Family that was a-okay with racial slurs, jokes, and ribbing that everyone dished out and received on all sides and both ends.

Haoles (whites) sometimes felt targeted. Hapas (mixed-race) were recognized by sight alone, but that didn’t stop us from asking, “What are you?” I knew what I was before my blood type and even my astrological sign. Race was a big deal, and at the same time, nobody cared. We were proud, and we took for granted that our ethnicities were reflected in our daily bread; our meals, a mishmash of American, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Polynesian, Portuguese, SE Asian, and Hawaiian.

We knew our sugar plantation stories, how Captain Cook “found” the islands, how he died at the hands of the Natives, our Hawaiian mythologies, ghost stories, songs, and history more so than anything else that went on in the Mainland. We knew we were different, special, but we also knew that we were part of a tribe who called Hawaii home.

And yet, oddly, as I grew older I couldn’t wait to leave all of it. I’d look up at the planes and wish I was on them.

After the coffin had been removed from the plane, Grandma demanded to see the body.

“Please, let me see my son. I need to know it’s him.”

“Do you remember what he looked like when you last saw him?” Asked the airman.

“Yes, of course.”

“Then let that be your last memory, the image you keep forever in your mind.” He looked down at the black casket standing between them. “Not this.”

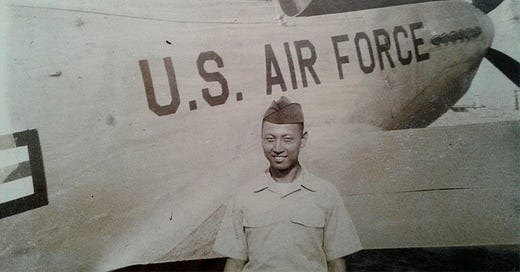

The church service at Punchbowl Cemetery was where I felt the true weight of what happened. Not when we were in the hospital, or flying back, or picking out the religious symbol we wanted for his grave. No, it was when I stared at the black-and-white picture of my dad placed on top of his coffin. I looked at nothing else until the ceremony continued outside.

Someone had given Mom the picture, and she held it tight. She wore a long black veil and looked as if she hadn’t stopped crying since Thailand. There was a white canopy shielding the folding chairs and the coffin was draped with the American flag. The gun salute made me flinch because I wasn’t expecting it, and it was loud. We watched the servicemen fold the flag, 13 times into a neat triangle, and hand it to my mother. She received the flag and sat down.

Later, we gathered around his raw grave and took photos, and later still, we took more photos at the house. Then after the pictures were developed, Mom put them in photo albums. They were big heavy things kept in an even heavier carved teak trunk that Dad had to have, despite this thrifty nature, paying a hefty $600 just to ship it from Thailand back to the States.

Mom pushed it out of sight into the back of her master bedroom closet. It was an amazing work of craftsmanship, high reliefs of trees with leaves, detailed elephants, and houses. Sometimes she put stuff on top of it, so I had to take things off before opening it. Then, I’d unload all of the albums. This is how I know we took photos of his funeral and afterwards.

Photos in Thai homes are often of the deceased and none of us needed a reminder of who we’d lost. But later, much later, Mom put up a framed photo of them together in Thailand when she was pregnant with me, but you can’t tell, she used to be quite petite. They’re sitting on the ground beaming at the camera. Dad’s wearing some god-awful 1970s striped pants. But they’re happy.

“Can I take this?” It’s a treasured photo, I’m selfish to ask.

“Yes.”

But flipping through the albums, I find it strange that on the day of his burial someone took photos of Mom with relatives and friends on a small sofa. Everyone is in black looking haggard and beaten.

“Who took these pictures?”

“I can’t remember.”

Mom can’t recall much from that time, but she remembers Grandma asking her if she was going to take us back to Thailand.

“I wanted better for you guys, so I said no. I never once considered it.”

These early days were extremely stressful, particularly for Mom, who, like a lot of women during that time, leaned heavily on their husbands. After the funeral, we were told we needed to leave our home on Hickam AFB. I don’t know how Mom did it, but she decided to return to Mililani where we had lived before. Thank god, Dad taught her how to drive.

I don’t remember the packing, the goodbyes, just the last day when we were getting ready to hand the keys back. Maybe Larry was at Aunty Thoy and Uncle Ron’s place across the street.

Mom approached me on the front lawn. “Did you close the front door?”

I nodded.

“No, no, no.”

I looked at her in horror.

“The keys are still inside the house! Why did you close the door? Who told you to shut the door?”

She hit me across the face. I said sorry and cried. But she kept hitting me, even after my nose started bleeding. I was frightened and ashamed of the red mess, but mostly of the beating on our front lawn in wide daylight.

“Jan! Jan!” Thoy yelled at her friend from across the street. “What are you doing?”

Mom broke down further.

Whether it was in Thai or English, or both, who can say. Thoy rescued me. Mom voiced her fears, the problem of the house keys inside the house, on the kitchen counter, but Thoy hadn’t recently buried her husband, so she asked Mom if she checked the backdoor. Plus, they had to clean me up. Thoy led us behind the house, and the door was unlocked.

Your mom was traumatized by the loss of your dad, and sadly, you were the victim of both your mom’s trauma and your own. You were at such a tender age … 🥲🫂💜

There's so much here to comment on. You capture being so young on that plane perfectly: the confused innocence of a barely-processed bereavement, juxtaposed with the joy of 'flying' a plane. (Kind, well meaning guys they were too). The conclusion is shocking, hard to read. I felt troubled afterwards. And your dad's "snake pants" - as they were known - are frankly awesome.