1.

When I was about 13 years old, my family and I went on a road trip across America. Well, the western to the middle part. Once when we were in a McDonald’s and after I had ordered (Mom let us do that), the nice woman behind the counter leaned forward and smiled.

She said as proud as a teacher, “Your English is very good.”

I was confused. I stared at her for a moment, trying to comprehend a compliment that I hadn’t earned, but I remembered my manners and said, “Thank you.”

2.

I had some sort of fantasy that I’d be able to speak Thai well when I moved to my mother’s home country. But as it turns out, learning Thai is damn hard. I used to think it was me, that I wasn’t practicing enough, that I hadn’t found the right ingredients to get me speaking like a local, maybe I needed to eat more chili peppers, but now I realize that it’s the Thai language to blame.

Actually, I have several excuses...

First, Thai is a tonal language and it’s got five tones like Chinese. (Vietnamese has six and Hmong has a whopping eight.) And this is a big deal. Many foreigners can get away with using mainly the mid tone, but look at my face. Look at me, I cannot.

Watching their faces while I try to speak is like watching cats trying to hang on to curtains, or misjudging the jump from the kitchen counter and flopping into the trash can. Meanwhile, if a white person fumbles with their language they clap, cheer, and confetti drops from the sky because they’re OBVIOUSLY a foreigner making an effort. I, on the other hand, am an Asian who should know better. Curtains.

Take the word maa, for example, it means different things depending on how you say it – it could mean ‘come’, or ‘dog’, or ‘horse’. And you’d think that given the context of a conversation, Thais would understand which word you were trying to spit out, but sadly, that’s almost never the case.

One time, Mom and I were leaving the mall and taking a red truck taxi back to my apartment. When the driver asked where I lived, I said Chiang Moi which is a street that runs parallel to the famous Thae Pae road in Chiang Mai. But I knew I used the wrong tone because Mom started laughing so hard she slipped off the backseat bench and started to fall out of the truck.

I rushed to her to help her back in, “Oh, god, what? What did I say?”

It took her some time to stop laughing, the driver shook his head, then got in the front and started the taxi. She didn’t know the word in English, so through hand gestures and halting English, and my exasperated guessing, I finally discovered I said pubic hair.

3.

I teach English. I do what most foreigners do in Southeast Asia, unlike in Cambodia where you can do anything you want on a visa, like own a restaurant, work in a shop, or an art gallery. I like teaching though – well, sometimes. I was a Waldorf teacher in Oregon, but as you can imagine, I’m not exactly considered the face of English language learning.

For example, when I first enrolled for intensive Thai classes at Payap University, my receipt from the Foreign Language Center enrolled me for intensive English. Apparently, someone concluded by looking at my photo (because photos are attached to every kind of form here) that I must have checked the wrong box.

So whether it was in Ecuador, Cambodia, or Thailand, I started each class with, “Guess where the teacher is from!”

My students are usually teens, but it wasn’t unheard of to teach adults or even retirees. It depended on what school I taught at and often classes were a mix of students in uniforms and adult professionals.

Anyway, when I first walk in, I take in their raised eyebrows, whispers to their classmates, and sometimes, their smiles. I relish this moment because I’m not the typical white teacher, and I can see the curiosity written all over their faces.

“Teacher, where are you from?”

Tilting my head, I smile, “Where do you think I’m from?”

“CHINA!”

“Noooo.”

“Taiwan.”

“Hong Kong.”

“Japan.”

“Singapore.”

“No, good guess though.”

“The Philippines!”

“Korea?”

I put my hands on my hips, as if to say, “Really?”

At this point they have started to slow down their guessing and have become confused.

“What other countries are there besides Asian ones?” I ask.

“Australia?” They sound less confident now.

“Canada?”

“England?”

When someone is finally able to guess, “America,” I can say, “Yes!” and then I try to get them to guess which state. They know California and New York and sometimes they know other states like Washington, or Florida, but generally speaking, I’ve stumped them.

After my poor hula dancing impersonation, someone guesses Hawaii. It helps to be from the islands because as they accept the way I look with the way I speak, Hawaii feels like a kind of compromise, a bridge, and then we can begin.

4.

I was waiting for my punctual friend at a popular restaurant in Chiang Mai when a waitress brought me two menus.

She said something in Thai, as she placed a menu in Chinese and a menu in Japanese in front of me—and she probably felt pretty confident that she had covered her bases.

I looked up and asked in my remedial Thai, what I hoped was, “Could I have a menu in English?”

Exasperated, she swept up both offending menus and left to retrieve one I could read.

5.

Another reason why speaking Thai is impossible is because most folks can meet you halfway. They know enough English, so we end up speaking a kind of Thaiglish, or they grab their English-speaking friend from the next shop over and you start the transaction all over again.

Most Thais want to be helpful, so when they see you struggling, and they’re struggling, they’ve left before you can continue to struggle – and that my friends is a huge part of learning – struggling. Please let me try, let me continue to struggle to get this right. But the outside world isn’t a classroom where teachers speak slowly, clearly, pause, and wait for your answer. So unless you have some patient interactions, practicing in the real world can feel impossible.

To be fair, it’s not like the queue behind you is thinking, “Oh, she’s trying to speak Thai, let’s wait a little longer”.

No, they come up to see what the hold up is, and they look at you like you’re a zoo animal. You start to sweat harder and stammer until you want to cry out like wounded prey from the hunt, eyes pleading, bugging out, “Helppp, oh, god, why can’t you understand me?”

6.

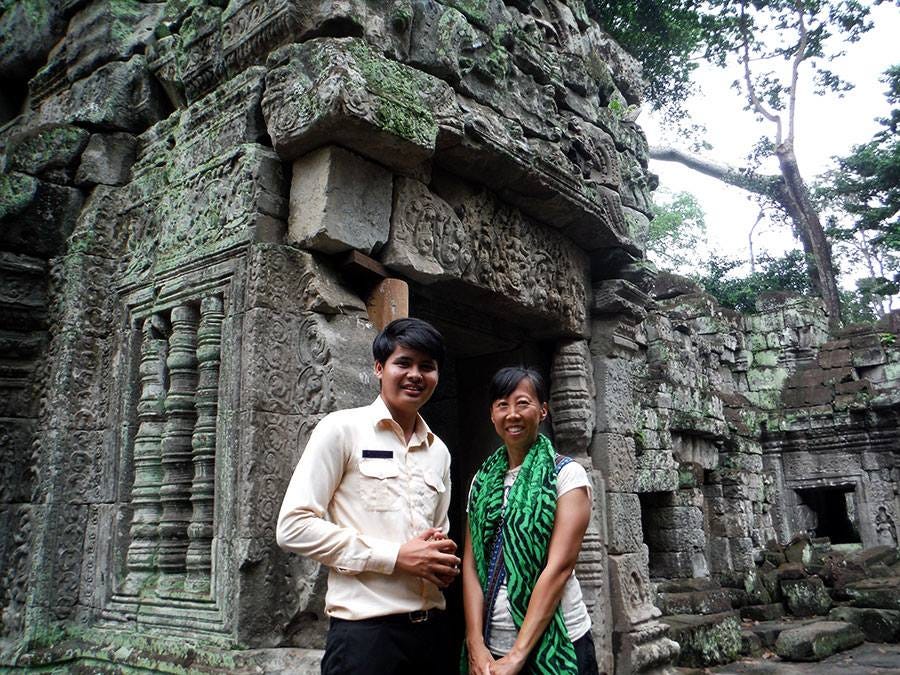

When I was teaching in Siem Reap before the pandemic, one of the new Khmer teachers asked, “Are you Chinese? Are you from China? Are you China?”

And when a new expat teacher saw me hovering near the teachers’ room because I was fumbling for my key card, she gently asked, “Can I help you?”

She assumed I was a student, but she wouldn’t be the first, or the last to make that mistake. I’ve had a student walk in and say, “Where’s the teacher?” because I was sitting down next to the students waiting for the rest of them to show up. Everyone laughed.

My colleagues would sometimes walk in my room to ask to borrow something or ask a question, only to look around the class baffled, until they spot me. “Oh! There you are!”

And then there was the time when the manager told me he had a very confusing conversation with the cleaning lady until he discovered she thought I was a Khmer teacher.

7.

Portland Oregon (had?) has a Saturday Market that is located in the Old Town (Chinatown-but-not-really-Chinatown) area that I used to go to regularly when I lived there. This was when I was in my early 30s. On this particular day, I was snaking in and out of the rows of vendors, enjoying the food smells and looking at what the booths had to offer, when I came upon an Asian woman’s booth.

She saw me looking at her stuff and excitedly asked, “Do you speak Chinese?”

“No, sorry, but I wanted to ask you…” I held up an item of interest from her table, but she had already turned around.

“Oh.”

And she remained turned around, until I left.

8.

When I first started to learn Thai, despite hearing it all my life, I was overwhelmed by the strange sounds, but gradually I started to hear the nuances, and better still, I began to learn Thai-isms.

For example, in American English it’s common to ask, “How are you?” We don’t even think about it, as it's part of our culture, and it’s a greeting that sometimes replaces ``Hello”, or “Hi”. But in Thai, they don’t want to hear about how you feel, they want to know where you’ve been, where you’re going, or whether you’ve eaten or not.

All the times my mom asked me, “Did you eat yet?” or “What did you eat?” came flooding back. I thought she was being motherly, but no, she was being Thai.

I began to dissect common Thai greetings. Perhaps asking a feeling question (How are you?) was considered a luxury. “Where are you going?” and “Where have you been?” is about action and a friendly curiosity probably stemming from simpler times. I don’t know. Of course, the irony is those questions in America would be considered intrusive, and maybe even offensive, depending on the context.

It took some getting used to, being asked about my business and my whereabouts from strangers or people I hardly knew. I even noticed that when I came back from the market Thais would look at my plastic bags to see what I was carrying. Sometimes, I’d even be asked what I purchased. All friendly conversation, as Thais love small talk.

By now, most Thais are used to foreigners asking them, “How are you?” They’ve grown accustomed to our way of expressing interest. But I love asking them their questions, especially, whether or not they have eaten. I like seeing their faces light up because when you ask “How are you?” there’s a different feeling behind their response. I suppose one that has little cultural significance. But to ask if you have eaten or not! Well, now, that shows you care!

Thai also uses a lot of onomatopoeias. Words can sound like what they are, as in tuk tuks (3-wheeled moto taxis) or words are named after the noise they make, jip jip is a bird singing, laughing is hahaha, and tokay is based on the mating call of the Tokay geckos. Suddenly, Mom calling a train, a choo-choo train, or a mouse, Mickey Mouse didn’t seem so bizarre and out of place.

9.

When I'm in Lamphun, visiting family, there’s no English menu. It's the quiet countryside compared to tourist bustling booming Chiang Mai. It's where my uncle, one of my many uncles, has his chicken and rooster collection, next to my aunt's beauty salon. And a few houses down is where my great aunt lives with her daughter who speaks enough English so that we can communicate a little.

A few blocks further is where my other aunt and uncle run a modest store selling local produce and curry dishes in to-go plastic bags, snacks, 20 baht fish, cold drinks, whiskey and rice wine by the shot glass. It's where I've watched my uncle give a rooster a bath and where I've seen them boil dead chickens, so they can pluck the feathers off their bodies.

It does no good to engage because my Thai isn't good enough to open doors. Because once I respond, the dam is cracked, and I am slapped into shape by my limitations. Northern Thai isn’t the same as Central Thai. My Thai is good for the city where many folks can meet me halfway with their English. But in Lamphun, they expect me to understand everything with none of the patience and pacing of a language learning program. So, it’s best if I play the deaf mute.

I am a deaf mute in my mother's culture and country. It’s where I sometimes choose to belong and where I sometimes disappear.

I’m a first generation American. The new Asian American: the ones who haven’t been taught the language, the ones raised in two worlds, the ones who don’t fit in because the Americans see you as Asian and the Asians see you as Americanized.

It's something I'm used to though. And over the years, as I’ve traveled, I find comfort and embarrassment in this. My identity, these days, hasn’t been so much a struggle, as it is an interesting reflection of how others interpret me. Identity is a fascinating set of circumstances that others place upon you, and it’s up to us to decide if it’s a cage, or a castle, or something entirely different.

I chose different.

Oh Lani, thank you so much for writing this. It is delightful to get a glimpse of your journey. I can relate to so many things you shared, especially this - "the ones raised in two worlds, the ones who don’t fit in because the Americans see you as Asian and the Asians see you as Americanized." For me, I have never felt belonged in Hong Kong, my hometown; whereas Australia feels like home to me, from the moment I landed there in my teens. But I am aware that many Australians still see me as a Chinese, never an Australian.

Also love, love, love this - "My identity, these days, hasn’t been so much a struggle, as it is an interesting reflection of how others interpret me. Identity is a fascinating set of circumstances that others place upon you, and it’s up to us to decide if it’s a cage, or a castle, or something entirely different.

I chose different."

Brilliant, Lani! I love this article about 3rd culture identity, and your intro into Thai culture. It reminds me of Arabic culture, where people always want to know 'how much have you paid' when you come away from the local Bazaar with anything. And as soon as you tell them, everyone insists that you have paid too much and should have bargained harder (unless you got an exceptionally good deal... 😅)

And this › "Identity is a fascinating set of circumstances that others place upon you, and it’s up to us to decide if it’s a cage, or a castle, or something entirely different.

I chose different." › is precious! 💗🙏