7. Mother, daughter, and the Holy Spirit

Welcome to the eighth chapter of Misfortune Cookie

These installments are read by the author. For the previous chapter, The moving coffin, please click here. It should be noted, however, that these essays can be read on their own. Thank you listening, subscribing, liking, and sharing. You rock!

“You know your daddy’s in heaven, right?”

I looked up at Grandma. “Yes.”

She smiled, chuckled a little and looked up. “He’s with God.”

My eyes followed her, but I didn’t really feel that I understood her.

“Do you know what heaven looks like?”

I shook my head.

“It’s beautiful. The streets are paved with gold. Gold! Can you believe that? The gates are made of pearls, and the angels sing all day. And Daddy is up there with Jesus.” She smiled at me through her tears.

I didn’t know what to say, so I said as little as possible during these exchanges. Even at a young age, I thought heaven sounded excessive. It wasn’t my idea of heaven, and I certainly didn’t believe that Dad was up there among the clouds. I wanted to believe her, and some days I did. But I was filled with doubt, too. It didn’t seem possible. Clouds aren’t solid.

Yes, I did spend some time contemplating the solidity of clouds. I also spent time praying to God, begging for Him to bring my father back.

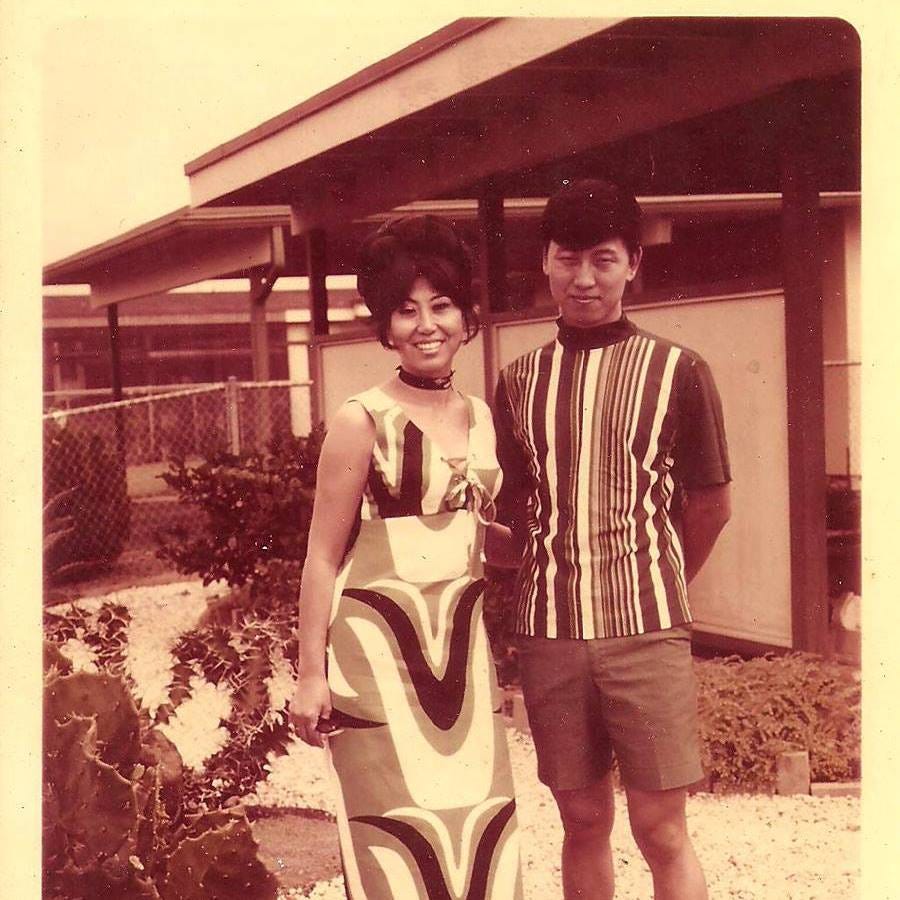

Mom became another woman. One that got dressed up for a fun night out, that left in the evenings and told us to lock the door behind her.

For a time, we went to church. Grandma’s idea, not Mom’s. Mom is Buddhist like most Thais, although these days religion seems old-fashioned, and now we worship the Almighty Internet. But Mom got baptized to please her mother-in-law, and I remember how angry it made me because I knew the idea of accepting Jesus Christ into her heart was simply lip service. It didn’t seem honest, but I was a kid who didn’t know about the power of peace offerings.

Apart from Grandma, Auntie Karen and the rest of the deeply Christian family, we lived our own lives. It didn’t matter how many cartoon Bible story books they gave us or how often they spoke of the grace of God, my mom took us to Thai festivals and parties. We kneeled before gold idols and Buddhist monks. We sat for long periods, like we would have in church, and listened to the drone of monks chanting. Larry and I didn’t understand any of it.

But there were times when we had to go to church without Mom. The best part of Sunday school was the punch and cookies at the end. When I was in the adult assembly, I was bored, unable to follow the sermon, instead I looked through everything that was within my reach, the Good Book with its delicate pages edged in gold, the donation envelopes, a pen or pencil, all made to slide into its places perfectly behind the wooden pews. I couldn’t even follow along to sing, and when they spoke in tongues, I simply stared and watched.

I usually sat between Grandma and Auntie Karen. They liked their makeup and figure-hugging dresses. Mother and daughter could not have looked more different though, especially since Auntie Karen dyed her hair Christie Brinkley blond. She was an attractive woman who looked like her white father rather than her Chinese mother. But she was the one who caused the family to part like the Red Sea. Somewhere in the middle of childhood, my contact with my Chinese cousins, aunts and uncles, ceased to exist because when family lines were drawn, we stuck with Grandma and Karen.

“Your dad made me promise to look after her.” Mom told me.

Much later I learned how troublesome Karen was, that Grandma used to call her son in the middle of night, begging him to go look for his sister who had gone “missing” again. Even though undoubtedly she was at a party, or with another man, Dad got in the car and crawled the streets of Hawaii Kai and beyond. Another time, mother and daughter showed up at our door unexpectedly looking for a place to hide and rest. It turned out Karen had gotten an abortion, but why they chose to our place, I’ll never know.

I’ll also never know if they were both deeply religious before Dad passed or only after as a way to assuage the loss. I don’t think Karen cared either way though. When I looked at the photo of all of us around Dad’s new grave, she was the one smiling brightly and beautifully at the camera like we were at a wedding. And while Grandma shared stories of her son, Karen never did of her half-brother, maybe because she felt second-best under his shadow.

Grandma once told me how guilty she felt that Karen grew up without a mom since she was such a workaholic. This ended up costing her marriage to Kenneth as well, who found attention and comfort in his secretary, as a result of his wife’s absences.

But Grandma made it up to her daughter. After Dad’s death, they were inseparable. Grandma worked as a server at the Hawaiian Hilton, and Karen stayed home watching TV, buffing her nails. She went to modeling school and later Bible college, but she never held a job. Mother and daughter moved frequently, and their phone number changed often. They were as mysterious as neighbors, showing up in our lives with consistent irregularity.

But during every visit she’d always say, “Grandma is very proud of you.”

I’d look down embarrassed, unaccustomed to praise.

“Grandma is also proud of you, Jan. Raising these two on your own. So proud.” She said fiercely. Tears were never far behind. Mom, equally awkward as us, would say “thank you” and we’d hug when it was time to say goodbye.

But as I grew older I wanted to meet the man whose last name I carried. I tried to broach the subject of Mr. Cox with them several times. I wanted to meet my grandfather, my dad’s adopted father, Karen’s father. I wanted to meet another person who knew my dad. Instead, Grandma told me this:

“You know, Ken contacted me the other day. He called from a hotel room. He told me that the hotel room number he was staying in was 666. Can you believe that? The number of the beast. I said, ‘Ken! How can you stay in that room number?!’ And he said, ‘Because I worship the devil.’ Your Grandfather is a devil worshiper. You cannot meet him. Never. I won’t allow it.”

But then many years later, perhaps after she had forgotten that she had told me about his devil worshiping ways, she said, “I was too hard on him. I should never have left him. He was a good man.”

I used to pretend I was dead in an attempt to get behind it. I wondered where my dad had gone and what it would feel like to be dead.

At night, I’d pull the covers over my head to create complete darkness. Sometimes I’d lie there taking peeks out of my sheets, other times, I’d close my eyes and tell myself, This is what death feels like. I am dead.

Perhaps I was meditating before I knew what the word was. I’d sink into the emptiness, get bored, a little hot, and then really hot and eventually throw the covers back. I’d come to the conclusion that nothingness was scary and not really what happens when you die. Trying to imagine what happened after you died was like trying to open your eyes when you sneeze.

In other words, it couldn’t be done. I couldn’t imagine not imagining, not doing, not thinking, not feeling, not seeing, not anything, but just being. But, you’re not really being, ‘cause you’re dead.

Whenever we met Grandma and sometimes Aunt Karen we’d normally go to a Chinese restaurant like Aiea Chop Suey or downtown at our favorite potsticker place. They didn’t cook and for whatever reason we never ate at either of our homes despite Mom being fantastic in the kitchen. Maybe it was better to meet on neutral territory, halfway, where no one had to pretend to like the other’s cooking. I’m not sure Grandma or Karen knew how anyway.

But for this particular occasion, we tried someplace new, with a lot of glass. It felt like we were in a fish tank on display, and we were having another one of our polite meals when Grandma decided to put her chopsticks down.

“What’s wrong with him?”

Mom and I looked around. “Who?”

“Him.”

Our eyes landed on Larry. My dear younger brother with his unfortunate bowl haircut.

“What’s wrong with him? He never talks. It’s not natural for a child.”

We were both quiet children, actually. Dad’s death plunged us into silence, but we were often praised by strangers and family and friends for being well-behaved. Hairdressers liked to ask me how old I was and then exclaim how mature I seemed. Although, I suppose I was more forthcoming than Larry. Sometimes it felt like he played the game, how long can I get away with not responding to adults.

“That’s just the way he is,” I said.

Mom and I used to joke that Larry would make a great judge one day. He’d sit in silence and dole out his right sense of justice. Or maybe he’d be a lawyer since he has an incredible memory. What is it they say about music? It’s all in the pauses between the notes.

“It’s not natural. It’s already been a long time.”

We all knew she was referring to her son’s death. I suppose it had been a while. Ten years had passed, but that didn’t stop Grandma from saying how much Larry looked like his dad. To be honest though, Larry looks more like Mom and I take after the Chinese side. It always grated me when folks made that mistake.

“Maybe he should go to Kahi Mohala.”

That triggered my mom, “What’s that?”

“What?” I got up from my seat and stood by Larry on the other side of the table. “No! There’s nothing wrong with him.”

I pleaded with Mom. “Kahi Mohala is where crazy people go. Larry’s not crazy. I won’t allow it. You can’t take him.” I was covered in cold sweat, terrified by the idea of Larry being taken away to the place we kids used to tease each other about.

“People with mental problems,” I pushed my head with my pointer finger, “go there.”

Grandma leaned back, “But something’s wrong with him. He’s too quiet. He should be noisy. He’s a boy!”

Perhaps she was comparing him to her son. Perhaps my father was more gregarious as a child, more charming, and while both boys suffered from missing fathers, that’s where the similarity ended. Dad had memories of an abusive father. He was probably happy when they left him behind in China, and his adoptive father, Mr. Cox, loved and cared for him better than his own.

Larry grew up in the dark where his dad was concerned. He had none of the memories that I had being two and a half years older. He quietly tolerated all the questions from thoughtful family and friends about his wonderful father while mourning the loss in a different way than his sister or mother. Larry’s life was no fairy tale where the protagonist can remember lullabies of a long-gone mother or a deceased father’s lingering soap scent by his crib.

He may have been given the gift of memory, but he had no memories to hold. Like an adult who gets throttled by the relentless questioning of a toddler, my brother earned his long-distance endurance legs by seeming nonchalant. Grandma meant no harm by her questions, “Do you miss Daddy? Do you love God? Do you pray every day? Do you read the Bible?” She hugged us and sometimes gave us cards with $5 bills which was amusing since Mom was far more generous, even giving Grandma money, bailing her out of trouble that Karen would get them into.

And when Larry never responded to her questions, she’d chuckle good-naturedly and declare, “you’re a good boy” regardless. She tried and we tried, but I’m not sure if it got us anywhere. Maybe that wasn’t the point.

“You won’t send him to Kahi Mohala, right?” I said.

Grandma, who divorced her first and second husband, then lost her son to a poor country woman whose homeland was the violent setting for his death, paused before replying.

“No.”

This is so engaging, Lani, but also tough. Family shisms and the loss of parents; they are hard to deal with and I admire your delicate balance between frankness and tact, with humour and pathos threaded through it all.

Hi Lani, I am really enjoying reading your story — your family's story. I can relate in so far as being a child observing the same odd, quirky and non-sensical (in a child's eye) trapping of our adult relatives and their friends etc. It must have been bewildering for you and your brother given the loss of your dad. Thank you for sharing.😊🙏💜